This is part two of the 12 days of Covidmas. Read part one here:

Covid is not a historically disruptive virus. This may surprise you. But when the history books get written, it will be the response to the virus that is of note, not the virus itself.

As I mentioned in the introductory piece, what we are seeing at a macro level is that there were about 2.8 million deaths in the U.S. in 2019, and largely due to Covid, that number is going to rise to roughly 3.1 million deaths in 2020.

There as well is the point that it is a more accurate paradigm to view Covid as increasing mortality by 10-15%, rather than seeing it as a whole World War Two of deaths, even though both are numerically accurate. This is because it is overwhelmingly leading to the deaths of old and sick populations rather than young or healthy ones.

But there’s more to say in order to really demonstrate that Covid is unremarkable historically, as this is such a departure from the conventional narrative.

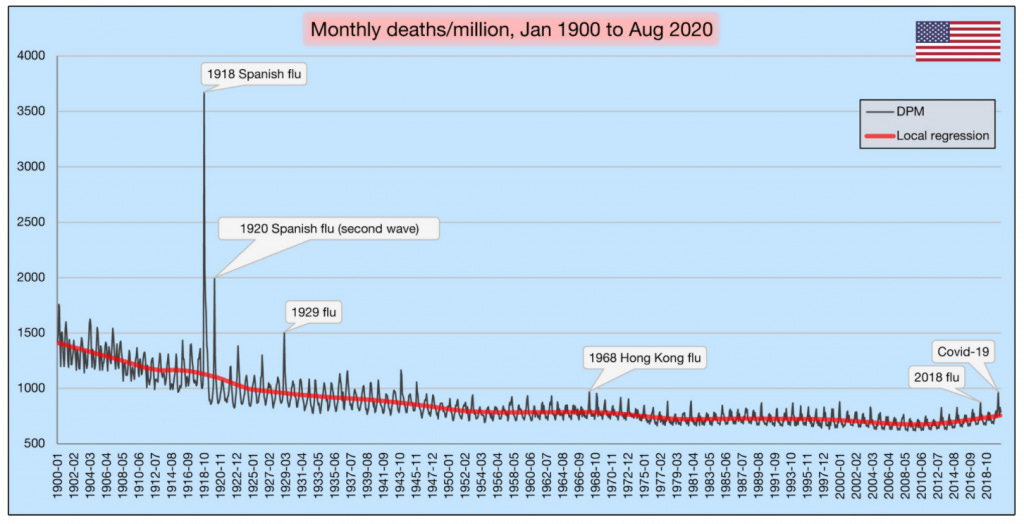

One way that we can look at this is by looking at the number of deaths per million people each month. This data is available on the CDC website. This work was done by Twitter user VoidSurf1, who has shared several threads on this, but I’ve spot-checked a few numbers and the data is accurate.

As you can see here, the Covid spike is visibly higher than previous years, and reaches the approximate level of the 1968 Hong Kong flu, which together represent the highest points since the end of World War Two.

As noted, this normalizes for our population growth because we are looking at the number of deaths per million citizens. But it does not take into account the aging of our population. In 1970, the median age of an American was 28.1 years old. Fast forward to 2019, and the median age is a full decade older: 38.4 years old (source). This is a substantial difference, and of course this extends into old age: we have a much larger portion of 80+ year-olds around today than we did fifty years ago.

We can adjust for this too, by calculating a death rate for each age bracket and then taking the average so that the mix of different ages is held constant. When we do that, here is what the monthly trend looks like:

This graph now is about as good an approximation that we can get to of how well our society has done at keeping people alive. The general trend is great, obviously! Science and technology have driven tremendous improvements over the last century. Awesome!

But this also shows what Covid really is if you strip away how we’ve reacted to it: a historical blip. We will have, for one year, stepped back all the way to… early 2000’s mortality, which was 10-15% higher than where we are at today.

Is that sad? One hundred percent. But think about this for a second: a generic year just twenty years ago was more deadly than our pandemic year of 2020. How on earth did we handle ourselves in such an insane and deadly world back then?

Another point to add context to this is just how incredibly minor Covid is when compared to the Spanish Flu of 1918. While even a normal winter was much deadlier back then, the Spanish Flu was a tremendous anomaly, jumping the (already high) death rate up almost 3 times. If we presume all those deaths were the Spanish Flu, then 75% of any death happening during that first wave were from the Spanish Flu. In contrast, Covid has stayed consistently at, again, 10-15% of the deaths happening this year.

So if Covid is just a mere blip on the radar, why then has our reaction been so drastic?

The answer is pretty simple: this is a social-media driven panic. It is, as Heather MacDonald put it recently, “more like the Salem Witch frenzy of 1692” than it is like any real pandemic.

Social media has evolved the world so thoroughly and quickly that we still do not fully appreciate the implications of it. Most prevalent here are two factors.

One – social media brings us all (digitally) closer together, creating rumor mills and environments once seen only in small towns or cliquish high schools, but now scaled to hundreds of millions of people.

Two – social media and the digital advertising economy have monetized attention, which has thus created a rat race for your eyeballs. Humans love to focus on a few specific things, namely sex and fear. Covid obviously satisfies the latter. But in the past 15-20 years we’ve seen hurricanes labeled as more dangerous, snowstorms have names to make them scary too! Each election is “the most important election of our lifetimes.” Most people think crime is going up, even though crime is going down. Covid is really just another piece in a broader fear-driven panic we are living through today.

If there is one lesson I’d want you to take away from today’s article, it’s this: fifty years from now, the impact of Covid as a disease will be a single tiny blip on a chart that will need a label for future school children to identify. But the societal implications of how we reacted and potential legislative fallout will be what the books cover.

If we are wise (I’m skeptical), then we can view Covid as a warning shot not just for pandemic preparedness (and yes, we do need that), but also for deescalating the social media fear spiral we are living through.

If we are unwise then we may learn neither lesson as we suffer many long-term harms not from Covid itself, but from how we freaked out about it.

Tomorrow we’ll take a look at risk, and how to assess it rationally.